Samir Savant — My Relationship with Music

12/5/2023

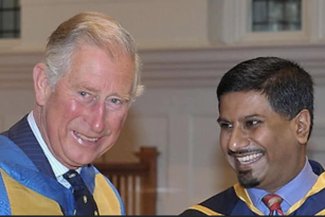

A personal blog article from HP Foundation trustee Samir Savant

Music has always been an essential part of my life, and I am lucky that this is where my professional experience and my personal passions come together. Although my parents were not musical, they recognised the importance of music education. They were immigrants to this country and wanted their children to have every opportunity, and so I had lessons in piano and violin from an early age. I also had Indian classical singing lessons, and was a member of the Manchester Boys Choir, which was my first taste of high-quality music making, including television work, major concerts and competitions, and international touring. I have been singing ever since, and still sing in several choirs (tenors are luckily in demand) and I founded the award-winning chamber choir, Pegasus.

I never studied music academically, but an enlightened teacher played me a recording of the chapel choir of St John’s, Cambridge singing the sublime Requiem by Duruflé, and I was instantly drawn to the warm, open sound. I decided to audition for a choral scholarship, got in and sang under the direction of the late George Guest and Christopher Robinson. My contemporaries at St John’s included countertenor Iestyn Davies and Andrew Nethsingha, who recently excelled himself leading the musical elements of the Coronation.

On graduating, I knew that I did not want to be a performer, but that I did want to be involved in management and making the magic happen, and so I studied for a Masters in Arts Management at City University in London. Two decades of marketing and fundraising positions followed in some of the capital’s leading venues including English National Opera and the Royal College of Music. Then I had my first position in general management, running the London Handel Festival, which brought together my interest in baroque music and Georgian history with of course my esteem for George Frideric Handel.

The annual Festival comprises several performances and creative projects in venues across London, including the international Handel Singing Competition, which has helped to launch major operatic careers. A personal highlight was the staging of Handel’s rarely-performed Berenice at the Linbury Theatre as a co-production with the Royal Opera House; it had not been performed at Covent Garden since Handel himself conducted it. I was working at the Festival in March 2020 when Covid-19 hit, and the ensuing lockdown forced us to cancel two-thirds of our performances, which had a devastating effect. As the year dragged on I was determined to organise a creative project which would give work to professional musicians and lift all our spirits. The resulting Messiah Reimagined involved live soloists and orchestra, all socially distanced in Handel’s church, while the choruses were pre-recorded digitally by hundreds of singers from across five continents. The premiere in the run-up to Christmas that year was special; Classic FM was our broadcast partner, and it was viewed on Facebook by global audiences of over 250,000. I was humbled by the comments from all over the world; everyone had really missed live performance, especially the huge sense of community and achievement which comes from singing in choirs.

I moved to Bristol in September 2021 to take up my current position as CEO of St George’s, Bristol, a 580-seat concert hall, converted from a 200 year old Georgian church, and a truly special space where we welcome the world’s greatest artists. Classical music is at the heart of our programme, and I was proud to host the first ever BBC Prom in Bristol at St George’s last year, but we have a wide-ranging calendar of events, including folk, jazz, contemporary, roots and spoken word. Music management as a profession remains sadly impenetrable to ‘outsiders’. I am painfully aware that I am one of very few people of colour in a senior leadership position, and I am proud as a trustee of the Harrison Parrott Foundation to be working to address this imbalance.

I was told that Bristol has more choirs per capita than anywhere else in the country, and so last summer we presented Bristol’s inaugural Festival of Voice, a celebration of the human voice in all its glorious variety, bringing together international artists with choirs anchored in their local communities. I was delighted with the response with over 1,000 singers from 30 choirs of all different genres taking part, including a flashmob ‘Hallelujah!’ chorus. This year’s Festival is even bigger and better. We started with our ambitious ‘Sing for the King’ project bringing together 650 singers (to celebrate Bristol’s 650th anniversary as a city) to sing Handel’s Zadok the Priest in the splendid setting of Bristol Cathedral on 1 May. We filmed it all and will send it to our new King with our civic best wishes.

Singing is wonderful because it is a universal activity existing in all world cultures, from the visceral appeal of Bulgarian choirs to the other-worldly quality of Mongolian throat singing, and you do not need to read music or buy an instrument. Both Messiah Reimagined and ‘Sing for the King’ demonstrate the appetite for mass participation choral projects, and the importance of singing for our mental health. I truly believe we are in the midst of a golden age of singing in the UK. There are many excellent choirs, led by inspiring directors, often singing incredible works by contemporary composers. There could be no better showcase for this than the recent Coronation, when the music was the envy of the world.

However, we cannot forget the need to invest constantly in music education, which is being eroded along with public funds for the arts. No-one must feel left behind and talent can only flourish if we are truly inclusive, and acknowledge and deal with the barriers to enjoying and performing music. In a modest but focused way, Harrison Parrott Foundation is doing its bit by supporting Open Up Music, in particular the development of the pioneering Clarion, an electronic instrument that can be played with the movement of a musician’s eyes.