Music, Madison Avenue style

14/2/2020

The Guardian newspaper featured HarrisonParrott in its early days, with this article by Gerald Larner from 1971

“They are brilliant, brilliant. Quite the best agents in Western Europe,” according to a music-publisher friend of mine. If so, Harrison and Parrott have achieved the superlative only 16 months after going into business together. Either that or, as some of their long-established rivals might suspect, their reputation has developed more quickly than their service to the artists.

It is true that Harrison/Parrott publicity has not happened by accident. It is, to a large extent, the result of a carefully planned advertising campaign, which has annoyed some of the more stuffy members of the profession. But their service to the musicians they act for is equally highly developed and equally unconventional. They define it as “personal commitment between manager and artist”.

Terence Harrison says the function of an agent is “to be convinced of the talent of the artist he is working for, and to support the artist in the inevitable bad periods. You know you have this loyalty, and you must be prepared to go with him all the way, right to the cliff edge.”

Jasper Parrott agrees, but in rather less emotional terms: “A really responsible manager simply must not think in the short term, but think in terms of an artist who will develop; an artist you can find a stimulating career for. I have never been interested in handling a terrific turnover of dates. I have always been more interested in a continuous relationship with a small number of artists or a developing project.”

Before they jointly got the sack Terry and Jasper worked in the foreign department of a large London agency. “For the first year we didn’t hit it off.” Terry, son of a Sheffield bus driver, and in his seventh job, was naturally suspicious when he was joined in his department by the son of the British Ambassador to Czechoslovakia, seven years younger and fresh from Tonbridge and Cambridge.

Terry had left High Storrs Grammar School at 15 and had worked in accountancy, insurance, the RAF (statistical analysis), selling adding machines “which did not seem to work,” the National Provincial Bank, and a merchant bank. When he came to Ibbs and Tillett, after writing 100 letters in a variety of artistic direction, he took a 50 per cent cut in pay in order to get out of commerce and into music.

Jasper, who is still only 26, says he had “considerable social advantages, which Terry definitely did not have. But I should tell you that Terry has a fantastic ability with figures.” That is one clue to the complementary quality of their partnership. Once they had settled their differences with a “terrific fight,” the partnership developed while they were still at Ibbs and Tillett. They became “too active, too headstrong. The atmosphere suddenly became restrictive as we developed our own contracts and loyalties.” So, when they refused to sign a contract they did not like, they had to go.

At that time, in October, 1969, Jasper might have left to help run a music centre in America, Terry to an orchestra. But in a matter of days and with no capital they had decided to form their own new-style artists’ management business. This was mainly because of the encouragement they received from some of the artists they had worked for at Ibbs and Tillett. Vladimir Ashkenazy joined them immediately, so did Lawrence Foster, offering to lend them £1,000 (which they did not accept), and Malcolm Frager, Rafael Orozco, and André Tchaikovsky. Another coup was Radu Lupu, whom Terry had gone to Leeds to hear (on Orozco’s advice) during the piano competition. He had interviewed him before the final and advised him, should he win, to see all the other agents and make his choice. Incredibly, since Harrison/Parrott was not yet in business, he joined them.

Two private loans and help from other agents (Howard Hartog in particular, and also Christopher Hunt, the first of the “young agents”) got them through the first six weeks, working from their flats six miles apart. “Fortunately, I don’t think anyone realised how chaotic it was,” Jasper said. But then they found a backer, a merchant banker and music lover now living in New York, who became the third partner. They acquired their present offices in Wigmore Street, at first in a “depressing and disgusting state” but attractive enough now, with four secretaries and an “astronomical ‘phone bill.”

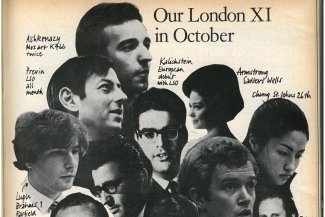

“We are considered to be very extravagant.” The series of full-page ads in “Music and Musicians” accounts for much of that, though they write the copy themselves (and with more sophistication every month).

What do the other agents think of it? Jasper: “Some of them consider to be…” Terry: …”infra dig…” Jasper: “Yes, that’s right. We have had a few brushes with them. But we do it for two reasons, for the sake of the artist, and as a PR exercise. It stimulates reactions, either favourable or unfavourable. At least no one has said we are an unimportant agency, and we are as much in view as any agency with five times our resources.”

On investigation the claim that their effect on the other agents had been to “split them down the middle” seemed to be true. Mrs Tillett who had dismissed them from her firm, could not bring herself to comment. “Ask them,” she said. But she did admit that she could “not really” approve of their advertising. “It’s not for us, anyway.” On the other hand, Basil Douglas, who has a smaller agency with about 100 artists, thought it “unreasonable to disapprove of publicity which is good for the artist. They have just started and have got about a dozen or so young and really starry artists. It is a good way to do it.”

Mr Douglas also gave a traditional view of the agent’s function, which “after all is to act as agent between the employer and the artist.” But he did not agree that personal service is impossible in the large agency, since the many who do not need it leave time for the development of others. “Every new young agency likes to think they have their own methods. All agents like to think they give a personal service.”

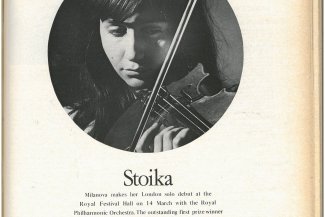

But the list of musicians who have joined Harrison/Parrott for the “personal commitment” as well as their business sense, is impressive. Anna Reynolds was one of the original set, and André Previn an early recruit. Joseph Kalichstein joined at about the same time, and then there was Kyung Wha Chung, Gerald English (from Ibbs), Christopher Seaman, Peter Frankl, Sheila Armstrong (also from Ibbs), Edo de Waart, Stoika Milanova and Uri Segal.

The list of those they have had to turn down is equally impressive. This, of course, is the agonising thing about personal service. At present they have 17 exclusively represented artists and they admit, “We have not given the service we hoped we would.” “Our artists are very young, very talented, and very vulnerable,” Terry says. “My own insistence on having a personal relationship has called for all my resources of energy.”

Not that they do it for nothing. According to Jasper, however, “Our service is a cheap as anyone else’s in the business, and cheaper than those that charge the new flat rate of 12 ½ per cent.” Harrison/Parrott have a special sliding scale with the biggest percentage on the first £5,000 of fees earned in a year – which ensures the continued interest in the firm of the more successful artists, at least until the end of the year.

No one has left them yet, presumably because the system works. Kyung Wha Chung, for example, joined them in January, 1970, when she was quite unknown. They could get no engagement for her until May, since when she has made a record and has had to turn down more than a hundred offers.

At present they are trying to do the same for another prize-winning girl violinist, Stoika Milanova, one of the next subjects for a “M and M” ad. Once they have got her career off the ground, they will no doubt make sure she is not overexposed. Kyung Wha Chung will give no more than 60 concerts next season, and Radu Lupu no more than 65 – in contrast to Rafael Orozco, the previous Leeds first prizewinner who, under different management at the same stage, would have been better advised to make himself scarce, after the style of Ashkenazy.

This wise husbandry of artistic resources is good not only for the artist and Harrison/Parrott but for us too. So much (too much) that happens in our musical life originates with the London agent – from some of the big festivals to the local music society who write for a 75 guinea pianist for March 1 – that it is important that the successful and influential agents should have their hearts in the right place.

Terry Harrison, for example, wants to help start opera in the North of England, which is the right place for me. Jasper Parrott is concerned about “so much suffering” by young artists on the long lists of the big agents: “They telephone their agents once every six months and are told there is nothing for them – so many young pianists, you know.” So the more young agents to look after them the better – until the concert managers start muttering about “so many young agents, you know.”